Why Do You Need for Tara Reade to be a Liar, and What Happens If She Isn't One?

Part 1 of a three-part series

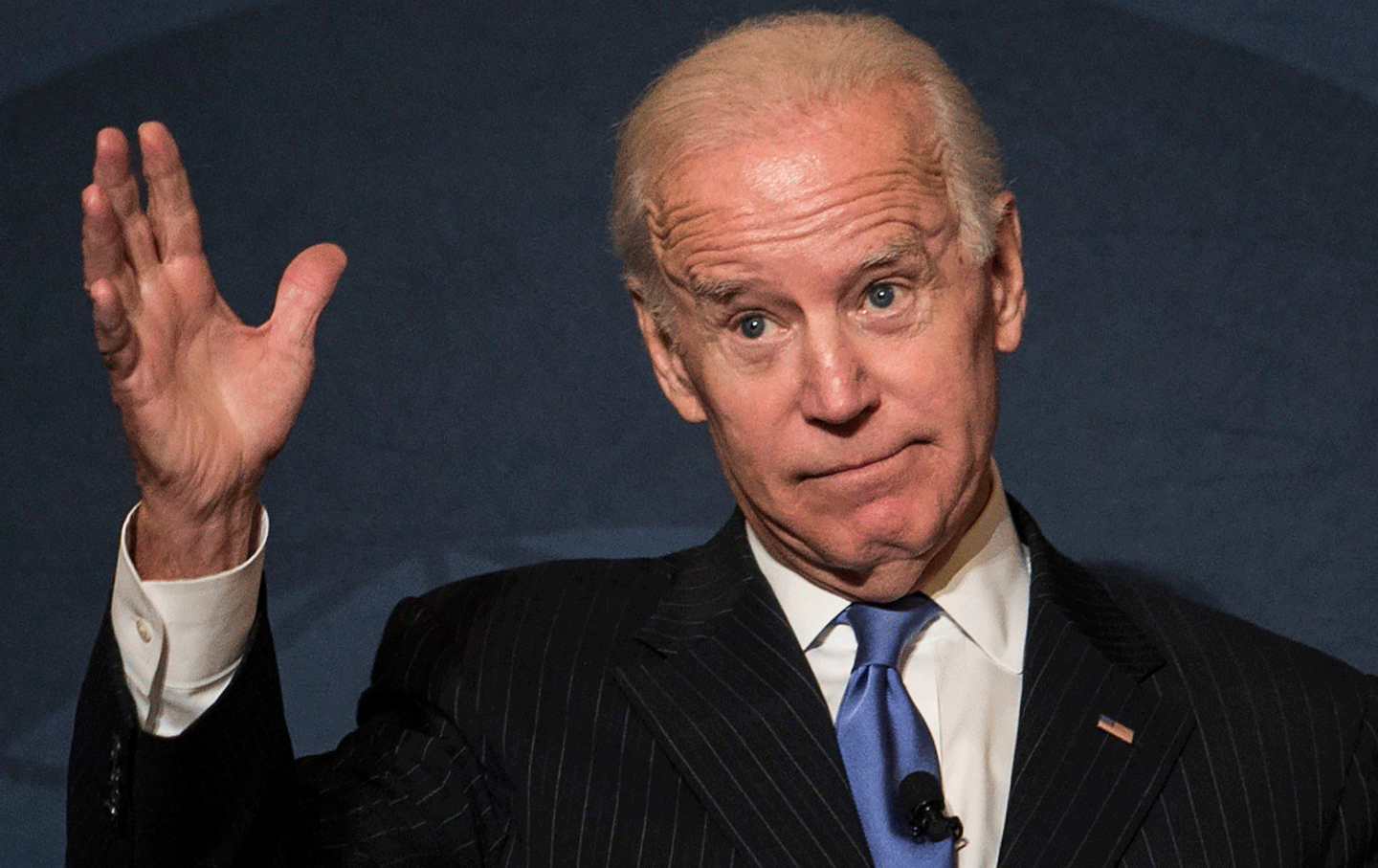

Image Credit: Ashlee Rezin

Recently there has been an escalated effort to get to the bottom of Tara Reade’s sexual assault allegations against Joe Biden. Since many of us with non-essential or work-at-home jobs have now been home for a couple of months, and are ready to think about something other than the coronavirus response, what better to obsess over than the presidential election?

Given President Trump’s response to the coronavirus pandemic, conducted with the same incompetence and malfeasance characterizing virtually all of his policy responses, November cannot come soon enough -- that is, if Joe Biden is elected. People sitting at home, already heavily burdened with anxiety, are desperate to do literally everything they can to prop up Biden’s candidacy and ensure a Democratic win in November.

But will they toss out all the gains of the #MeToo movement while they do it?

In this three part series, I will talk about how we can analyze sexual harassment and assault claims in a survivor-focused manner, and how we can use that analysis to think and talk about Tara Reade’s allegations.

It’s a pesky complaint that just won’t go away, even though virtually everyone wishes it would. Tara Reade has come forward to report that she was sexually assaulted by then Senator Joe Biden in 1993, when she was a member of his staff. After the assault happened, she said she reported Biden’s misconduct to others in the office (who deny remembering that she did so), and to the Senate Personnel Office (although thus far, no copies of this report have surfaced). She reports telling family members (her late mother and her brother), a neighbor, and a coworker, all of whom say Reade told them something about a traumatic sexual assault incident sometime in the 90s, even if they’re not clear on all the details or knew that it was Joe Biden who did it.

The Intercept first reported Reade’s account of the assault, having previously proven willing to report stories that more established mainstream media publications would not. (The Intercept was the first media outlet to report about Christine Blasey Ford’s leaked letter to Sen. Dianne Feinstein concerning assault by Brett Kavanaugh.) If you’ve read the book “She Said,” where New York Times reporters Jodi Kantor and Megan Twohey have enough material for an entire book about how they broke the Harvey Weinstein story, you’re already familiar with the great lengths that media publications must go through to break stories about sexual harassment and assault. Our defamation laws require that these allegations be leveled with great care.

Regardless of what you think about whether those laws discourage truthful stories from being reported, it is undeniable that this exacting level of scrutiny means that many stories that ended up being validated as true took a considerable amount of time to be shared publicly. It is also undeniable that for all the post #MeToo improvements made in the media’s harassment reporting, there is still a prevailing belief that if the story doesn’t rise to journalistic standards of reporting, then it must be false. (This isn’t helped by President Trump’s insistence that so much verifiably accurate reporting is nonetheless #FakeNews.)

Not that there’s not enough evidence, but that it’s false.

Philosophers can and have expounded infinitely on the meaning of truth and the true/false binary. I’m here to say something that I know will be controversial (not like any of this topic isn’t).

It is time to throw out the true/false binary when we analyze sexual harassment cases.

It’s not meaningful, it’s not helpful, and it harms survivors.

(Be sure you’ve signed up as a Substack newsletter subscriber to get parts two and three delivered to your inbox later this week. The series will also be available on Medium.)